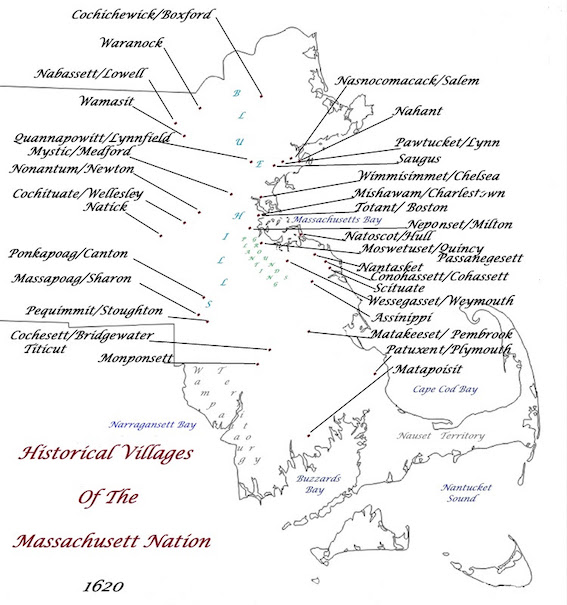

Founded in 1860, Emmanuel Church is located on land once used by the Massachusett Tribe for fishing in the estuary of the Quinobequin (now Charles River). Acknowledging this is an expression of our appreciation and a small, first step on the Way of Love, toward respect and accountability to Indigenous or First Peoples, who continue to suffer as a consequence of genocide and forced removal perpetrated by white ancestors of European descent. Our next steps have to do with actions to end violence directed toward them, which occurs when their histories are erased, cultures are trivialized, labor is exploited, and resources are seized. As the current occupiers of this territory, we must amplify First Peoples’ voices, honor their dignity, and repent of our complicity in their oppression.

The Massachusett tribe was matriarchal. According to their tribal history: [1]

Women of the tribe trapped small game, gathered shellfish, wild grains, greens, and herbs for food and medicine. The women of the tribe owned and tended the planting fields and preserved the harvests….The women also built and owned summer huts and winter longhouses, in which tribal members lived. The women were potters, basket weavers, wood gatherers, and fire keepers. Women took an active role in decision making along with the men of the tribe.

Archeological evidence of fishing in the Back Bay dates back more than 5,000 years. [2] In 1634 a mill dam had been constructed at Watertown, which prevented the herring and alewives that had provided livelihood for the Natick Tribe from spawning up river.[3] When another dam surmounted by a toll road was built across mudflats to Boston in 1814, it prevented the tidal flow from flushing sewage out to the ocean and created a giant cesspool.

Westward view from Statehouse (1858) showing the Receiving Basin south of Beacon St., which crosses the Mill Dam

Filling in the marshy area enclosed by the dam (upper left of 1858 photo) was viewed as an improvement. In 1862, Emmanuel Church was the first building completed on Newbury Street (above and left of the pond visible in what became the Public Garden). The wealth of people seeking luxury housing nearby had come largely as a result of the exploitation of brown people.

Since their arrival in New England colonists had been enslaving indigenous people even before African-American slaves were imported. Our church was founded by white Abolitionists, some of whom had direct experiences with enslaved people and whose wealth could not be separated from the larger economy, which relied on slave labor. Our first rector Dan Huntington, who later became the first bishop of Central New York, was born and died at his family’s homestead in Hadley, MA, where prior to and during the Revolutionary War his grandparents had inherited and purchased enslaved people, whom they probably held until slavery was abolished in Massachusetts in 1783.

Jemar Tisby writes: [4]

Anti-racist progress can only be realized if people treat race, religion, and politics as distinct but inseparable and interrelated factors. America will not see peace between different racial and ethnic groups without working for change in faith communities, as well as in politics and law. Racial inequities are the result of racist policies, which have been justified by religion, especially Christianity… Our generation has the opportunity to make different choices, ones that lead to greater human dignity and justice, but only if we pay heed to our history and respond with the truth and courage that confronting racism requires.

We still have meaningful work to do, Emmanuel Church. Thanks be to God!

Villages of the Massachusett Nation in 1620. Image credit: The Massachuett Tribe @ Ponkapoag: https://massachusetttribe.org/our-history

- Massachusett Tribal Life: https://massachusetttribe.org/ .

- Boylston Street Fishweir.

- Carla Cevasco, “Damming Fish and Indians: Starvation and Dispossession in Colonial Massachusetts”, The Junto: Blog on Early American History, 18 June 2019.

- Jemar Tisby, Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019 (NY: Random House/ One World, 2021).